Paul Rose, CEO at OFTEC, argues below that electrification is not the only answer to the process of decarbonising off-grid homes.

There is no question that off-grid heating must be decarbonised in order to contribute to the UK’s challenging carbon reduction targets. But electrification, one of the options endorsed by government’s recent Clean Growth Strategy and RHI Scheme, is not the only answer.

Of course, OFTEC, as the trade association for the oil heating industry, would say that wouldn’t we?

But our opposition is based on clear factual evidence that large scale electrification just isn’t realistic on many grounds, including: high installation and running costs; additional generation and infrastructure costs; performance; carbon reduction; return on government investment; practicality; and social impact. And we put forward an alternative, credible solution.

We believe the simplest way to decarbonise homes that currently use oil is to convert them to a low carbon bio-oil. This route is backed by recent industry reports from the Royal Society of Engineering and the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology which state that bio liquid fuels could make a significant contribution to future energy supply and ‘will be needed if the UK’s ambitious decarbonisation targets are to be met’.

Other sectors already employ bio-liquid fuels such as HGV road transport, shipping and aviation as well as commercial off-grid heating, and with development and sustainable production ongoing, we expect that a low carbon liquid fuel for heating could be readily available by 2022.

In the meantime, we propose introducing a nationwide oil boiler replacement programme to incentivise the upgrade of the 400,000 older standard efficiency models still in use across England and Wales.

This would provide the immediate carbon reduction and energy efficiency benefits urgently required to help the UK meet its Fourth Carbon Budget obligations, whilst ensuring boilers are ready to switch to a liquid biofuel once it becomes available within the next five years.

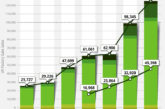

Clearly this practical, attainable solution flies in the face of current government thinking, which remains focused on replacing coal, oil and gas heating with other renewable technologies, primarily heat pumps and biomass. Tariffs for the domestic Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) have increased and commitment to the flawed scheme reaffirmed to 2021 in an attempt to encourage greater consumer take-up.

But this route to decarbonisation, as deployment figures since the scheme was launched three and a half years ago show, simply will not work.

The facts

Let’s look at the hard facts to see why electrification isn’t right and bio-liquid heating is. (This is based on a typical three-bedroom, semi-detached house with a 16,000 kWh heat requirement):

1. Installation cost: An air source heat pump (ASHP) currently costs c. £6,000-£8,000 or more to install, excluding additional insulation and radiator upgrade costs which are almost always required. By comparison, the cost to install a high efficiency oil boiler using a £400 government incentive available under a boiler replacement scheme (a stimulus previously used successfully) would be just £1,600 – or free for the poorest households under ECO. A further estimated £250 would then be requiredat a later date to adapt the boiler for bio-oil.

As most heating upgrades are distress purchases made when a system breaks down, price will likely remain the driving factor for most consumers. So unless the cost of renewable heating technologies drastically reduces, take up will remain viable only for the wealthiest minority.

2. Running costs: Under our scenario, it currently costs on average £894 p.a. to run a high efficiency oil condensing boiler, compared to £1,681 p.a. for an ASHP (source: Sutherland Tables, October 2017). With oil prices forecast to remain low in the medium term, how many homeowners will actively choose to almost double their fuel bills by installing an ASHP? At this point it is difficult to predict the price of a low carbon bio-oil but as suitable fuels are already being produced, and leveraging economies of scale that would come from increased take-up for various transport sectors, we are confident the eventual cost will be remain competitive.

Switching from oil to LPG has also been touted as a feasible route to reduce carbon emissions from off-grid homes, particularly as an alternative bio-gas fuel is set to become available next year. However, with the average annual cost of LPG heating currently over £630 more than oil (Sutherland Tables: October 2017), and the price of a bio-gas likely to be even higher, again, it’s doubtful many consumers will choose to substantially increase their fuel bills via this option even if they can afford to do so – which the majority simply can’t.

3. Infrastructure cost: Roll out of heat pumps on a large scale would require additional electricity generation capacity and upgrades to the distribution network to meet increased demand. With less than 30% of electricity currently generated from renewable sources, this proportion would also need to be greatly increased if decarbonisation remains the goal, and the financial burden of these changes will fall mainly on the taxpayer. In contrast, our solution is based on an established supply chain infrastructure, so no extra cost is necessary and, although bio-fuel production capacity will be required, this will most likely derive from the private sector, driven by the much larger needs of HGV transport, shipping and aviation.

4. Performance: To work effectively, ASHPs require properties to have an EPC rating of C or above. With 85% of oil using homes in England rated as E, F or G (source: Consumer Focus report), it will prove either cost prohibitive and/or wholly impractical to sufficiently upgrade these properties. Conversely, a new condensing boiler will deliver increased heating performance regardless of whether additional energy efficiency improvements are made, and if they are, these will only further raise performance.

5. Carbon reduction and government return on investment: In our independently verified example, the domestic RHI would pay out £7,182 over seven years for the installation of one ASHP into one household, delivering carbon savings of 24.43 tonnes over that time. For the same government spend, 18 households could be helped via a boiler replacement programme, producing a combined carbon saving over seven years of 201.6 tonnes – eight times more than the ASHP option. Following the cost of a minor boiler adaptation, switching to a bio-oil would further reduce carbon emissions – potentially by approaching 100% using an ultra- low carbon fuel.

6. Practicality: Low temperature ASHPs require larger radiators and/or underfloor heating to work effectively as well as additional building insulation, all of which are too costly and impractical to retrospectively install for most households. The learning curve for consumers to understand complex renewable systems is also steep which deters many, and with installer know-how still evolving, the scope for sub-standard consumer advice, installation, and performance is significant. However, replacing a standard efficiency oil boiler with a condensing model is a straightforward switch. The conversion to a biofuel would also prove simple with only minor modifications to the burner unit required. And with an already well-developed network of qualified and accredited installers, high standards are assured.

7. Social impact: More rural than urban households are in fuel poverty (14% vs 10%, source: DECC Annual Fuel Poverty Statistics Report 2016) and many more struggle to pay their heating bills, even those on oil which has remained the cheapest of all major fuels for almost three years.

These households simply can’t afford the high upfront installation costs of renewable heating technologies and, even if they could, switching to an ASHP would, in this scenario, likely increase their heating costs by 64% (source: Sutherland Tables, September 2017). This would force many more into fuel poverty and to live in cold homes with the associated health risks which would undoubtedly further increase the already unacceptably high rate of Excess Winter Deaths in this country.

On the other hand, swapping a standard efficiency oil boiler for a condensing model would immediately reduce running costs by some 20% and take many households out of fuel poverty. A further benefit would be a likely reduction in Excess Winter Deaths, for which cold homes are a major contributory factor. A competitively priced liquid biofuel, leveraging economies of scale from the HGV and aviation supply chain, would continue these benefits. This is a wake-up call to government. We need to employ decarbonisation measures that will produce results now, not carry on wasting valuable resources and scarce budgets on idealistic schemes which continue to fail.

The intention behind OFTEC’s strategy is not to prolong the life of oil heating for the benefit of our industry – there is far more at stake here. It is to put forward a realistic alternative as the current options on the table are just not fit for purpose.

With 25 years of experience, OFTEC knows the off-grid market and the facts speak for themselves. Greening the fuel via our proposed two stage approach is the answer.